The British Infantry Rifle, or Baker Rifle, 1800-15

Before we get to the rifle it is worth noting that the principle weapon of the British infantry and all others throughout the Napoleonic Wars was that of the flintlock smoothbore musket. The British musket was know as the Brown Bess, most of which were obtained from the East India Company. The Board of Ordnance in 1797 ordered gunsmiths only to produce the 'India Pattern'.

The musket had a 39 inch barrel and could also be fitted with a bayonet which was a triangular section blade about 15 inches long (the musket could still be fired with a bayonet fixed although the rate of fire was reduced). This was an improvement on an earlier version which was plugged into the muzzle itself and rendered the musket unusable

Unlike most of the British Infantry, the 95th and a few others were issued with rifles. These battalions where entrusted with rifles because it was felt that the rifles greater accuracy and distance could make a marked impression on the outcome of any battle or skirmish. They where not adopted through out the British Army as a whole as they where slower to load and it was felt the quantity was better than quality.

Rifles were not a new invention during the Napoleonic wars, they had been around for over 150 years, in fact the first patent for a rifle was taken out by Arnold Rotsipen in 1634. The British army had dabbled with rifles before and the first mention of their use is in 1751, but all of these early rifles were imported and foreign made.

In 1775 the British Military bought some German rifles to trial, by the end of the year, Viscount Townsend, the master general, was satisfied with the trials and asked the government to obtain the Kings permission to purchase 1000 rifles. He did not wait for the response and in Jan 1776 sent a preliminary order for 200 rifles from Germany.

Negotiations were opened with the Birmingham trade for the remaining 800.

A rifle was sent to William Grice, gun maker, so he could make an official pattern. After this was approved, orders were placed for 200 each with Grice, Benjamin Willetts, Mathias Barker and Galton & Sons at 3 guineas per rifle.

The situation changed in 1776 when Capt. Ferguson of the 70th Regiment trialed his breech-loading rifle to the British military. The trial was a success. Firing at a rate of 4 shots per minute over a distance of 200yds. The master general decided no more muzzle loading rifles should be made ‘ as a new construction of Capt. Ferguson’s is approved.’

An order was placed for 100 of Ferguson’s rifles to the same gunsmiths making the muzzle loading rifles.

In March 1777 Capt. Ferguson was placed in charge of training 100 recruits from the 6th and 14th Regiments in the use of his rifle. In May 1777 these new riflemen arrived in America with a supply of green cloth for uniforms. They were involved in the attack on Brandywine Hill and played a major part in the success of the battle. They suffered heavy losses and Ferguson was wounded. Whilst Ferguson was recovering his rifles were disbanded and incorporated into the light companies of their old regiments. The Ferguson rifles we placed into store and further use or trials were not continued. The Ferguson did have some shortcomings, the stock was weak, it required some skill to operate, and it also had the disadvantage of not being able to use standard cartridges.

The only identifiable original Ferguson rifle from the original 100 made is in the Morristown National Park Museum. 49 inch long, 34 inch barrel, 0.68 inch calibre, rifled with 8 groves.

In Jan 1800 the adjutant general wrote to Col Coote Manningham placing him in command of a corps of detachments from 14 line regiments ‘ for the purpose of its being instructed in the use of the rifle.’

Trials of English and Foreign rifles took place at Woolwich in Feb 1800. Bakers rifle had 7 grooves with a quarter turn, most of the day had a three quarter turn. Baker argued it was easier to load and simpler out in the field.

In March 1800 Ezekiel Baker was given an order for pattern rifles and barrels.

Initially two types of rifles were purchased one with musket bore and the other with carbine bore. In March 1800 the wheels were set in motion for the manufacture of the first 800 rifles to the Baker pattern. The gun makers Egg, Nock, Baker, Pritchett, Brander, Wilkes, Wright, Barnett and Harrison & Thompson shared this first order. Cost of each rifle 36 shillings.

In Sept 1800 a further 100 were ordered with improvements ‘ last approved by Colonel Manningham’. This improvement included a box in the butt.

The musket bore was objected too due to requiring too much exertion when loading and also excessive weight. Instead the smaller .625 calibre carbine bore version was adopted with seven square groves making one complete turn in ten feet (a quarter of a turn in a 30 inch barrel). The rifle length was approx. 46 inches, barrel length approx. 30 inches, weight approx. 8 lbs and with bayonet fitted approx. 10 lbs. All baker pattern rifles were browned from the start.

The Baker designed rifle for infantry was soon considered as a cavalry weapon. In 1801 Baker supplied carbines rifled for the Life Guards.

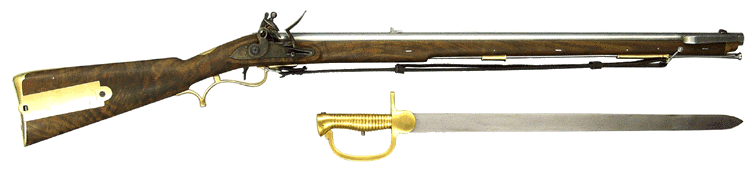

The locks of the rifle we marked “Tower” and “G.R.” under a crown. The stock was made from English walnut with a brass patch box in the butt. The brass trigger guard was a distinctive shape enabling a firm grip of the rifle for precise trigger let-off. The buttplate and the sideplate were made from brass. The stock had a raised cheek piece on the left of the butt. The barrel was attached to the stock with three flat, captive wedges. The fore-end cap and ramrod pipes were brass and the 30 inch ramrod had a rounded end. The sword bayonet was based on a German model. Henry Osborne in Birmingham was responsible for the first prototype and consignment. The sword bayonet was 23 inches long and was clipped on to a metal bar attached just behind the muzzle

Considering all of the Baker rifle components, the lock saw the most variance, particularly during the Napoleonic years. There were four basic changes in design and a significant number of minor variations. Some were mechanical, but mostly they were minor decorative or hand finishing touches, such as border lines. Early models had the rounded lockplate and swan neck cock. It was a reduced-size India Pattern lock. The second type, an adaptation of the New Land Pattern lock, had a flat lockplate, and a flat ring-necked cock. Some of these had raised pans and roller steel springs, some had the small leaf sprig engraving at the point of the tail of the plate, although otherwise void of decoration, aside from the standard markings. Others had the double border lines engraved on the plate and body of the cock.

About 1806, a third type of lock appeared. This had both a raised pan and a safety bolt let into the tail of the lock plate, and was fitted with a flat ring-neck cock. The plate itself had a stepped down tail and the entire lock was somewhat smaller than the earlier patterns. The raised pan was rapidly dropped in favour of a cheaper and less complicated ordinary pan. The sliding safety bolt was also considered an unnecessary refinement for the elite 95th. The modified New Land Pattern became the standard, but all of these locks were used concurrently, making it difficult to classify or precisely date any rifle from the lock alone. In 1822 production reverted to the first type, having the rounded lockplate and rounded swan-neck cock.

It is difficult to judge the extent of the issue of the baker pattern rifles, as they are given no official name in government records. It was only in Victorian times that it became to be known as the Baker rifle. (In our re-enactment regiment the words ‘Baker Rifle’ are banned, as the original 95th rifleman would not have known it as this. If a rifleman utters these words within earshot of an officer or NCO it will normally be followed by an order to run around the camp with the ‘British Infantry Rifle’ above his head.)

By March 1806 over 10,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry carbine barrels were being made. 3,000 of each type were to be rifled and set up, the rest complete except for the rifling and then held in store.

Over 30,000 baker pattern rifles were manufactured during the Napoleonic wars compared with 3 and half million muskets.

Cartridge charge was 4 drams; balls weighed 22 to the pound although some units preferred 20 to the pound to ensure a tighter fitting.

The last manufacture of Baker pattern rifles took place in 1838, when London gun makers set up 2,000.

Baker pattern rifles claim the distinction of having the longest service life of any rifle used by the British Army, it continued in service up to 1851 when they were used in the Kaffir wars. The rifle was used in almost every war in the world during its time, including against America in 1812, used by the Mexicans at the Alamo in 1836 and again in the Mexican wars.

A good example of the rifles greater accuracy is that of rifleman Plunket who on the 3 January 1809 near Cacabellos, shot and killed the French General Auguste-Marie-Francois Colbert to prove this was not a fluke he then proceeded to shoot the Generals Trumpeter. he accomplished this feat by laying on his back with the rifle sling looped around his right foot, one of the positions recommended for rife shooting. The distance is believed to be about 300 yards.

Another good example of the rifles accuracy is from Rifleman Harris

"I remember a fellow named Jackman getting close up to the walls at Flushing (During the Walcheren Expedition 1809), and working a hole in the earth with his sword, into which he laid himself, and remained there alone, spite of all the efforts of the enemy and their various missiles to dislodge him. He was known thus earthen, to have killed with the utmost coolness and deliberation, eleven of the French artillerymen, as they worked at their guns. As fast as they relieved each fallen comrade did Jackman pick them of."

Bibliography

British Military Firearms, 1650 - 1850 by Howard L Blackmore